Anyone who has witnessed an epic battle between honey bees at the entrance to a beehive understands the seriousness: it is intense! What is happening, and why? What are consequences – to the attacker and to the attacked? Does this behavior require intervention from the beekeeper?

Most environments will experience nectar dearths – times of the year when flowers are not producing abundant, or even sufficient, nectar. In Oklahoma, we can experience this between June and September but especially in July and August when we have less rainfall and high temperatures. At this same time, the honey bee colony population has expanded to its peak. During dearths, honey bee foragers become desperate for nectar.

Desperate times breed desperate measures – William Shakespeare

The smell of honey, particularly from an open hive, attracts foragers. Additional foragers gather; early foragers have communicated to nest mates about the new found source and begin to attract even more bees. Soon, in a very short time, hundreds of bees are actively, and aggressively, onsite. However large the colony, it is no match for hundreds or thousands of foragers on mission to collect nectar. Weak colonies are a relatively easy target for marauders looking to get some sweet food. Robbing ensues.

Initially, robbing bees – robbers – sneak through the hive entrance. Once inside the hive robbers quickly rip cappings of stored honey, slurp up the cell contents then fly back to their colony. Once guard bees discover robbers, the fighting begins. While robbing could happen gradually over the span of hours or days, during dearths the robbing activity quickly escalates within minutes.

Colonies with lower bee population, for example new splits, and colonies that are weak due to pest or disease problems, such as a high varrao mite load, are vulnerable to robbing activities. In these cases, a flurry of robbing activity can easily wipe out an entire colony and its stored honey resources in a matter of minutes.

Even when the colony being attacked is able to successfully defend itself against robbers, potential problems exist:

- Honey stores are exhausted

- The adult bee population declines

- Colony defenders come in direct contact with attackers who may be carrying varroa mites or diseases.

Similarly, defenders come in close contact with the attacking bees. This contact could contribute to high varroa mite loads, parasites, bacteria, diseases or other infectious agents that are spread during combat. For these reasons, it is critically important to immediately address robbing.

How do we know when a colony is being robbed? Are there telltale signs and symptoms? Yes! Robbing bees contribute to frenzied activity at the front of the entrance. Watch and you see this behavior! Also, robbers explore the entire hive by hovering around the entrance, swaying to and fro, and around the sides and back as they look for an entrance where they can sneak past guard bees. Anywhere there is a scent of honey, robbers could be found.

Guard bees patrol the entrance(s), on watch for intruders who have an unfamiliar odor. If/when a robber lands at the hive entrance, it is the responsibility of the guard bees to detect and ward off these intruders. ideally, they’re going to be detected and attacked by guard bees. Strong hive – those that have a high population – will have more guard bees who can better protect the colony. Conversely, weak colonies have fewer guards to patrol the entrance and become more susceptible to intruders who rob.

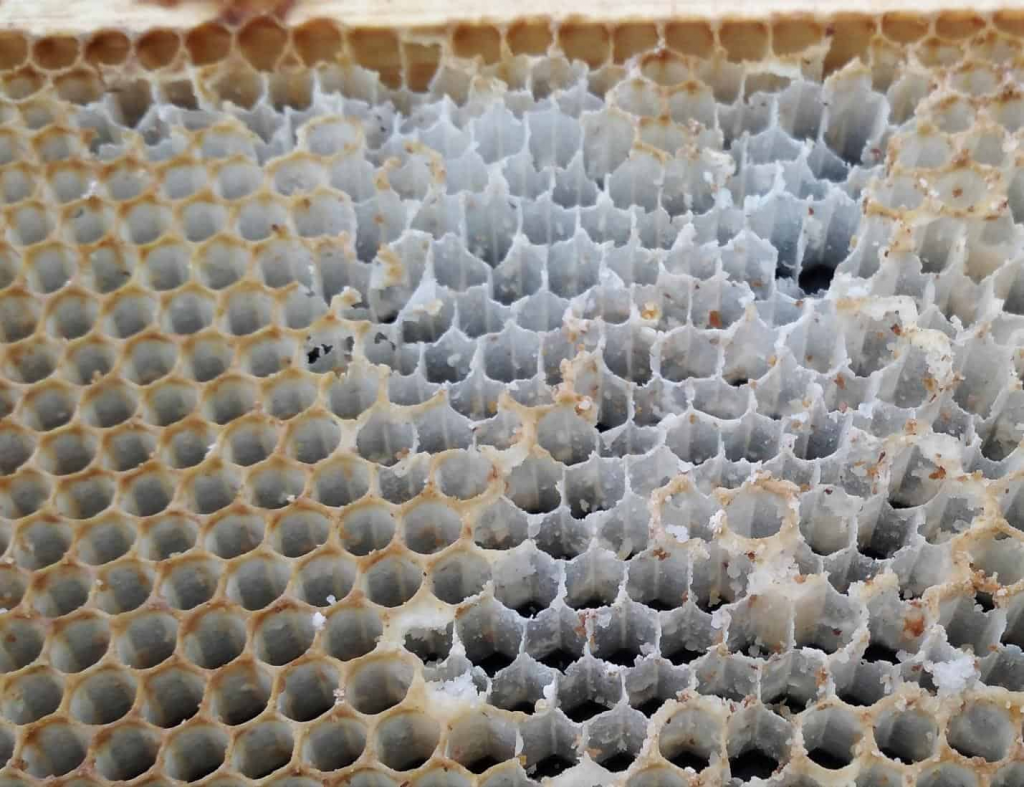

When a robber is detected, the guard bee releases an alarm pheromone which stimulates the nest mates to join the crusade in defense of the hive. From the outside, fighting between the colony’s members and the intruders is noticeable: bees wrestle and grapple. If the robbing is allowed to continue, and the colony is unable to tamp down the intrusion, within an hour wax cappings can be seen on the bottom board of the hive and on the ground in front of the entrance. Dead bees will begin accumulate on the ground as bees die while fighting. One other sign: robbers track honey as they leave the hive and their light brown footprints might be visible.

Opening a hive that is, or has been robbed, will shown wax cappings from the honeycomb will be on the bottom board. Another sign of a hive that has been robbed will be a reduced population due to the deaths of bees from the colony from fighting and heat exhaustion.

How do we know the difference between a colony that has a very strong honey flow with lots of forager activity and a hive that is undergoing a robbing attack? Look at the entrance: are bees fighting, biting or grappling, or trying to sting each other? Do we see any dirty footprints or a pile of dead bees? If so, the colony is being robbed!

How do we prevent robbing? Robbing is common during a dearth so it is important to miminize the amount of time we keep open the hive while inspecting; keep inspections brief. If removing honey frames, do not open capped honey and move the frame away from the hive or place it in a boxed container. We can maximize a colony’s ability to guard itself by keeping the hive healthy and populated. Increase space between hives in an apiary minimizes a colony’s susceptibility to robbing too as it reduces the smell of honey between hives. When open feeding, have the feeder a distance away from the hive; avoid Boardman feeders as they are attractants. An inside feeder is less attractive to robber.

Be aware that colonies that have survived a robbing attack are more likely to be defensive in the following weeks. Use caution when opening up these hives.

How do we stop a robbing attack in progress? Act fast! A weak colony that is being robbed will die within a few hours if there is no intervention. Reduce the entrance to the colony to about 1/2 inch in width – the size of one or two bee bodies. This opening allows returning foragers to enter and leaving foragers to exit yet small enough for guards to easily defend it. Another option is to staple a mesh screen that provides ventilation but confuses robbers. A wet sheet can be placed over the colony until the robbing has subsided. This allows the resident bees to find their way underneath the sheet back into the colony, but the robbers are directed away from the colony entrance.

References

- Picture credit: https://beeinformed.org/

- “Robber Bees!”: https://bluetoad.com/publication/?m=5417&i=550516&view=articleBrowser&article_id=3262667&ver=html5

- “Robbing Behavior in Honey Bees”: https://journals.flvc.org/edis/article/download/128187/129252

- “Honey robbing: could human changes to the environment transform a rare foraging tactic into a maladaptive behavior?”: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214574521000134?casa_token=KQTLfmiJS1IAAAAA:RS3zP3bDGU5jDvYIzp4vGYQNg2WCsoBYIcIUIFTFJXgUmYhTNShlnRuEKLque_MpDTTJi5RF2TJY

- “Honey robbing causes coordinated changes in foraging and nest defence in the honey bee, Apis mellifera“: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347220303808?casa_token=iHZYXnN02WYAAAAA:Nx5GRQtscVzsFx1IWpkNrllf3mOX1qGcyQPwXhWLxjQJsZaZ98npp7–46oCnwTetshEDlLP5oF2