Dr. Karl von Frisch, a zoologist, studied communication among bees. His work significantly increased the knowledge of the chemical and visual sensors of insects. He successfully deciphered the language bees, termed the “waggle dance”, used to convey information to hive mates about important and abundant resources for their colony. These resources could be nectar, pollen, water or propolis. For this and other discoveries, he won the Nobel Prize in 1973.

His early experiments included the placement of a beehive in a field with a single nectar feeder. Dr. Frisch and his team of researchers sat and watched the bees inside their hive. They observed the bees performing a waggling behavior.

Why were these bees waggling? Dr. Frisch discovered the bees used this form of communication to direct their foraging hive mates to the resource. The encoded message, which became known as the waggle dance, provided information about the resource’s distance and direction from the hive.

This waggle dance can be considered a miniature reenactment of the foragers flight to the resource. Her dance is composed of a starting point on the honeycomb, a walk to an ending point, then she circles back to the starting point and repeats this process. During this display her wings are buzzing, her abdomen is waggling and her feet are pounding the wax “dance” floor. Every part of this dance communicates information to her dance followers, including the angle of her dance run that indicates the direction of the food source and the duration of her dance that indicates the distance to the food source.

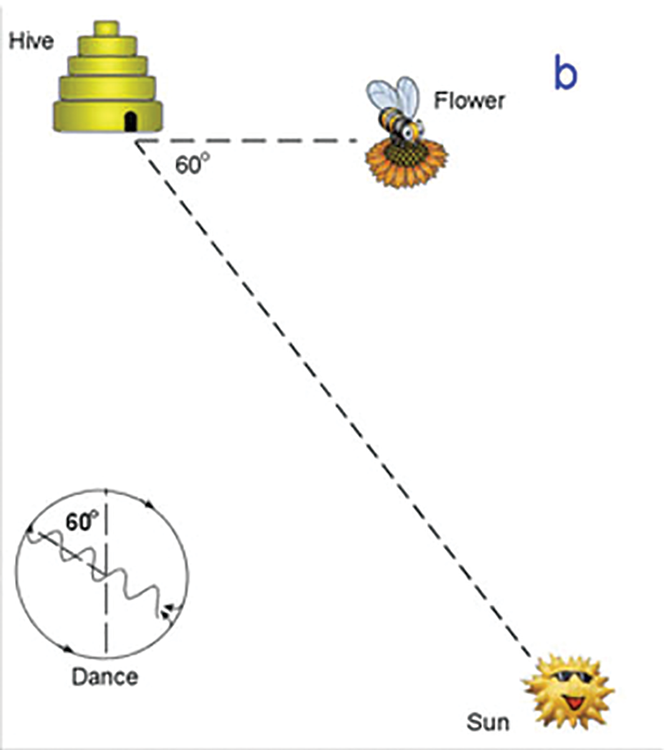

Bees use gravity as a baseline, the calibration and reference point, and “up” is exactly 180 degrees from “down”. Outside the hive, “up” points directly to the sun, no matter the sun direction in the sky. For example, a dance of 60 degrees to the left of “up” in the hive would be translated to 60 degrees to the left of the sun outside the hive.

The distance to the food source is communicated by the duration of the dance run: a longer run would mean the food source is farther away from the hive and a shorter run would indicate the food source is closer. A one second run is approximately one kilometer.

More research provides us with more data about how resource locations are transmitted through both the dance and dancer:

- Scent – the scent of the flower is detected on body of the dancer by those bees watching the dance. This scent helps foragers point to an exact flower source at the location whose coordinates are communicated by the dance.

- Vibrations – the dancer’s feet vibrate the honeycomb which is felt by hive mates. An experiment showed bees dancing over empty cells recruited three to four times as many dance followers and, thus, foragers, as those dancing on sealed cells. Sending vibrations “long distance” can alert would-be foraging bees who are looking for dancers.

- Repetition – A dance repeated over and over is communicates the quality of the food source and is meant to capture the attention of hive mates in an effort to solicit more foragers to seek out the source and bring back nectar, pollen, water or even propolis. A dancer’s scent marks the starting point on the wax floor so their dance begins at the same point.

- Speed – The dancers excitement is communicated by the speed of her dance.

This form of communication is unique. Only one other species has this ability: human beings! When we give directions, for example to a restaurant, we use similar forms of communication: words, actions, perhaps providing a sample of the food. But the honey bee performs this dance in near total darkness! So, how do hive mates perceive the angle (direction of food source) and length of dance (distance to food source)? Dance followers “listen” with their antennae outstretched so that the dancer’s moving abdomen touches and displaces the follower’s antennae. The dance follower understands gravity is the baseline and calculate the angle based upon their sense of gravity to the angle at which their antennae have been displaced and relative to the position of the dancer.

Different races of bees (Carniolan, Italian, German, and Caucasian) have different “dialects” or “accents” of waggle dances that vary in the number of waggles per run.

Like humans and other animals, bees need sleep. Sleeping bees can be found at the margins of a cluster or beehive. A sleeping bee is still and does not move. Their brain activity is reduced. This sleeping activity occurs after a long day of collecting nectar, pollen and propolis or when the weather is bad and the forager has no other jobs. But, how does a would-be dancer recruit sleeping foragers? After she has unloaded her nectar and pollen load, she grabs inactive bees with her forelegs and shakes them to attention with her abdomen. Once she has an audience, she performs her waggle dance. Researchers believe this “shake signal” is used to alter a bees activity and meant to trigger a change in tasks.

Another dance used in combination of the waggle dance is the tremble dance. When a returning forager cannot find a receiver bee used for unloading a harvest, the tremble dance is used to recruit receiver bees. She trembles her body and walks throughout the hive communicating to the appropriate-aged hive mates that nectar receivers are needed.

When a food source site is overcrowded or begins to fail, returning foragers communicate the situation by pressing themselves against their hive mate forager and giving a short, high-toned beeping noise. This “stop signal” effectively inhibits waggle dances that communicate the location of the resource.